Stellar Evolution Primer

In teaching stellar evolution for third year students, there are a few things that link tightly to the physics covered earlier in the class, and are worth highlighting.

Important Physics Reminder

The Virial Theorem

The entire process of stellar evolution is playing out in self-gravitating spherical systems with mass and radius , where there is a relationship between the gravitational self-energy of the system and the thermal energy in the gas. Since these two energies are related through the virial theorem, we can note that

where we have used a general form for the gravitational self energy and the constant is a constant of order unity that depends on the density distribution of the object. A uniform density sphere has . We have also expressed the number of particles in the system in terms of the mean particle mass .

Note that the temperature is inversely proportional to the radius, so that as an object gets smaller, it will also get hotter. Recall also that, in the absence of any source of support, the system will collapse. The virial theorem gives that half of the gravitational energy will go into heating up the gas (as per above) and the other half is radiated away. Since objects radiate energies at a rate given by their luminosities , the time it takes for an object to contract substantially is set by the Kelvin-Helmholtz timescales .

In general, as a stellar core contracts and heats up, one of two things will happen.

-

The star will reach the threshold temperatures and densities require to ignite a higher stage of nuclear fusion. For example, the temperatures could reach the temperatures needed to start the fusion of He into C under the process.

-

Alternatively, the core could become supported by electron degeneracy pressure. This source of pressure will provided the necessary support to keep the star in a hydrostatic equilibrium without nuclear fusion and the collapse will halt.

Degeneracy Pressure

The equation of state for (non-relativistic) degeneracy pressure is

where for in SI units. Of note there is no temperature dependence on the equation of state. This becomes important if the temperature of the gas becomes high enough to ignite fusion inside a degenerate gas. Also of note, the mass-radius relationship for objects supported by degeneracy pressure has a negative index. The pressure required to support an object of mass and radius is . If this pressure is provided by electron degeneracy pressure, as above, where , then

This result means that higher mass objects have smaller radii.

Evolution on the Main Sequence

Stars on the main sequence are, by definition, fusing (1) hydrogen into helium (2) in their cores. Low mass stars are fusing primarily through the pp chain and medium and high mass stars are fusing primarily through the CNO cycle. Either way, the net effect of this fusion is to change the chemical composition in the core of the star from H into He. Or, in terms of mass fractions, decreases toward 0, increases toward . This means that the mean particle mass is increasing:

.

Each fusion chain reaction replaces four protons in the core with only one helium nucleus. Since the gas pressure in a star is

,

the amount of pressure provided by a gas at density and temperature will decrease. This means that the density and temperature of the core must increase to provide the pressure to support the star, increasing the nuclear energy generation rate and thus the luminosity. Thus, stars on the main sequence are getting more luminous over their lifetimes. The Sun formed with and will increase to about before it evolves off the main sequence.

Low mass Stellar Evolution

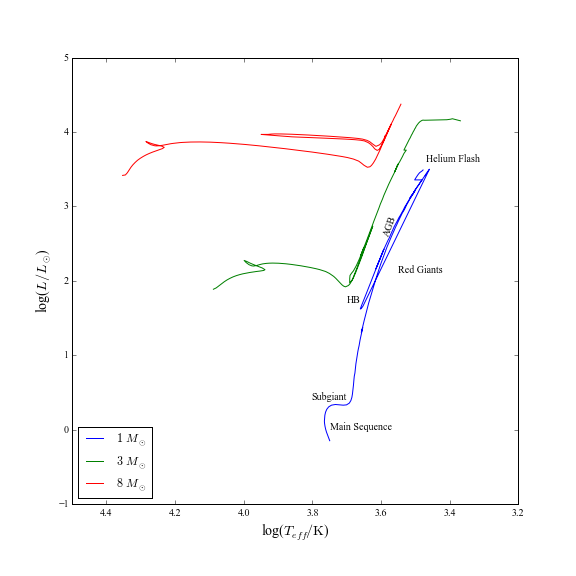

Here we mean stars with masses . We base our discussion of stellar evolution on these stars, and then describe the changes with mass in terms of this basic evolutionary scheme. See below for some figures that show how these stars are moving the HR diagram.

The Subgiant phase

These stars have radiative cores and radiative-plus-convective envelopes. For our purposes, the core means the part of the star that is undergoing nuclear fusion and the envelope is the inert outer layers that are not participating in the fusion process. The radiative nature of the stellar cores means that the material is static and a given parcel of gas remains at the same radius in the star. Since the temperature and density profiles in a star are highest in the centre and decreasing with radius, this means that the nuclear energy generation rate will be strongly centrally peaked and it will remain so over the life of the star. In terms of energy generation, this means that matter at the centre of the star is will fuse its hydrogen into helium at a faster rate, depleting the hydrogen content and arriving at a depleted state first . In this gas, fusion will shut off, but the gas will be hot and surrounded by a region of the core that is still fusing hydrogen. This gas will also be isothermal since it is not producing any fusion within it. Instead it will be held at a constant temperature set by the energy generating region around it.

As the star continues to fuse, this inert, isothermal core will get larger and the fusing region move to progressively larger radii. In this time, it transitions from being a core-burning star into a shell-burning fusion source. Shell-burning stars obey something called the mirror principle, which is an observation gleaned from the models that when a shell contracts, the envelope of the star will expand and vice versa.

There is a maximum mass for the isothermal helium core before it collapses under its own self-gravity. This is called the Schönberg-Chandrasekhar limit and is about 10% of the star’s mass. At this point, the isothermal core contracts and heats up on the Kelvin-Helmholtz timescale. During this contraction, the core, and shell-burning source shrink, meaning that the envelope expands. More of the mass will become convective. The contraction is eventually halted by the onset of degeneracy pressure.

The Red Giant Branch

At this point in the evolution, the star is at the base of the red giant branch. It consists of a degenerate He core with a shell burning source on top of it. As the shell source continues fusing the hydrogen into helium, the He ash builds up in the degenerate core, adding mass to it. As the mass of the core increases, its radius decreases, because of the mass-radius relationship for degenerate objects, the radius of the core gets smaller. Following the mirror principle the shell burning source (and the degenerate core) will heat up and the envelope will expand. The red giant will increase its luminosity at roughly constant surface temperature . Thus, it will appear to move “up” the red giant branch.

This evolution occurs on a nuclear timescale and will take nearly years a star. During this phase, the core gets smaller and hotter, approaching the threshold temperature for fusion, K. All stars reach this temperature when the core mass is about . Once He fusion ignites, it provides an energy source to its environment, which heats it up. Under normal conditions, this local heating would produce an increase in pressure, which would cause the gas to expand and reduce the fusion generation rate. This thermostatic mechanism keeps fusion in our Sun stable. However, in a degenerate gas, the equation of state has no sensitivity to temperature and the perfect gas component of the equation of state is much smaller than the degenerate component. (Note that the combination of the two equations of state isn’t as simple as just adding the pressures, but it will suffice for our discussion.) This lack of a pressure sensitivity means that there is no thermostatic process that will reduce the rate of fusion generation. Instead, the local heating will prompt the nuclear fusion under the process to increase much more (). This increase in temperature leads to a runaway fusion process and our truism: Nuclear burning in degenerate matter is unstable. This is just a nice way of saying a big He thermonuclear explosion goes off in the centre of the star. In their quiet, understated way, astronomers call this the Helium Flash. The amount of energy is not enough to destroy (unbind) the star. Note that, the helium flash could do so for lower mass stars, but no such stars have ever evolved off the main sequence. The flash provides enough thermal energy input to raise the temperature throughout the core and to settle into a perfect gas equation of state (and pressure support) again. The star then stabilizes on the Helium burning sequence.

The Helium Burning Sequence

These stars are undergoing fusion of He into C in their core. They have a H burning shell source (using the CNO) cycle and radiative envelopes. Since all the stars evolve from the ignition of a core, all these stars have a roughly constant luminosity of . Their surface temperatures can vary depending on whether there is mass lost during the movement onto the HB or the metallicity of the star. This means that, in a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, they will all lie on a horizontal line, leading to the other name for such stars: the Horizontal Branch. Most solar metallicity stars end up on the red side of the branch where they are called the Red Clump.

The Asymptotic Giant Branch

HB stars will evolve over another years on the main sequence and build up a C/O core that contracts and becomes supported by degeneracy pressure. At this point, they move onto the Asymptotic Giant Branch. These stars have a convective envelope, a degenerate C/O core and two nested shells of H and He burning. Like the RGB, these stars deposit material on the C/O core, causing it to get smaller and hotter. If these stars reached the internal temperatures of where fusion could ignite, they would proceed to another phase of fusion. However, the shell fusion in these stars gets sufficiently intense that it begins to force off the outer layers of the stars. This process happens in pulsations: the shell source builds up thermal energy, pushes off the other layers which reduces the pressure on the shell source and then its luminosity. The envelope of the star settles back onto the shell, building up energy again, which then pushes out. This is the thermostatic mechanism at work, but the pulses are much larger. These pulses throw off the outer layers of the star, which are observed as planetary nebulae and are some of the most amazing pictures we have of stuff in space. Here are some cool Hubble pictures.

After the thermal pulses on the Asymptotic Giant Branch throw off of the whole outer layer into a planetary nebula, the remnant is a hot C/O core, supported by degeneracy pressure. We call this object a white dwarf and they show up in the lower left-hand corner of the HR diagram.

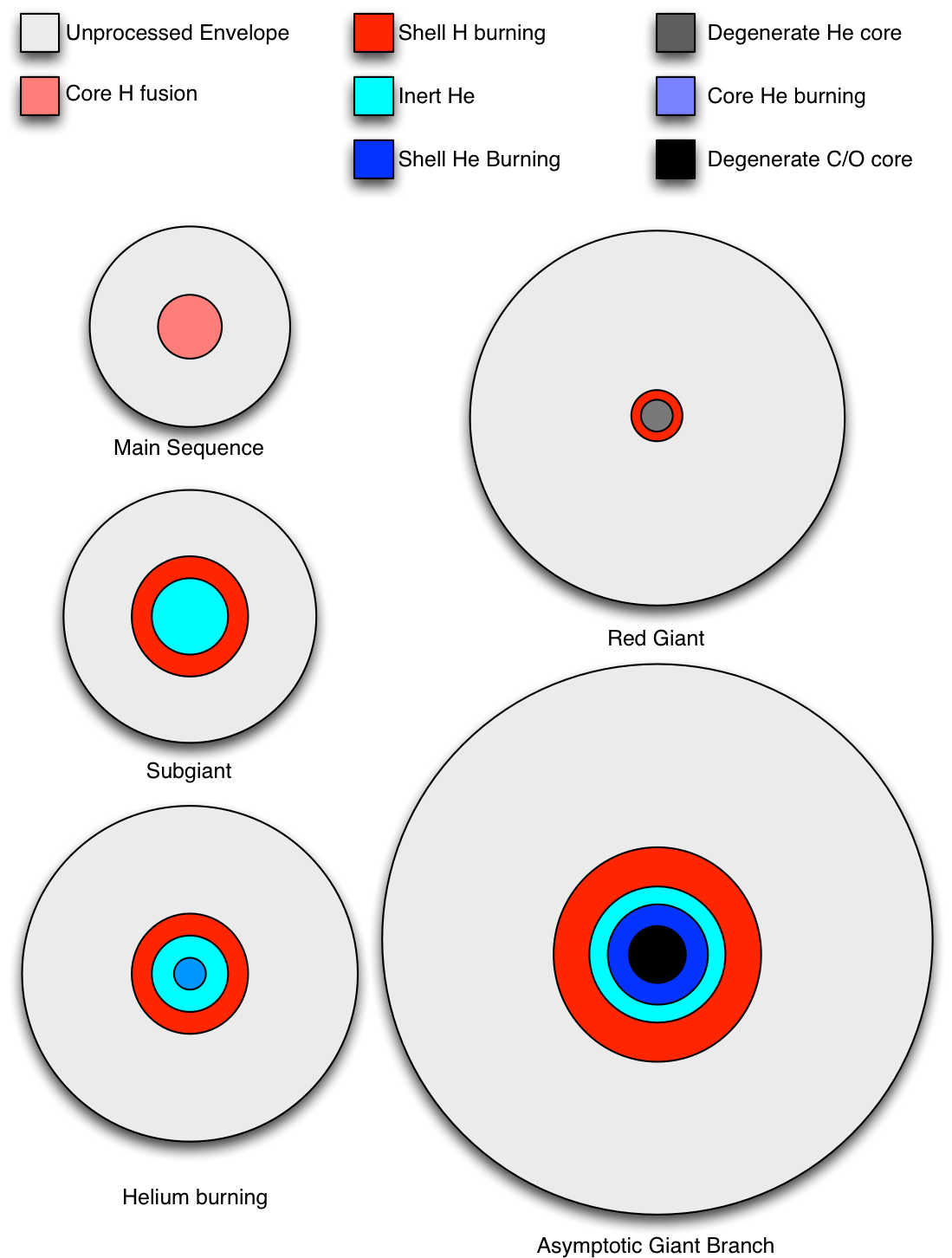

Star Structure

The diagram above shows the cutaways of the evolution of a low mass star at different stages of its evolution. It’s worth noting that the figures are very much not to scale, and the transitions between the stages are gradual. The diagrams are just to remind you of relative ordering of the components of the stars.

Evolution in the HR Diagram

The above discussion focuses on the behaviour of the interior of the stars with some attention to the envelope. However, since we can only see the properties of the stars from the outside, the observable parts of the stars that matter are reflected in the envelope. To that end, the evolutionary tracks of stars are generally described in how their envelopes are responding to their interior / core changes. This leads us to talking about how stars “move” in the HR diagram, but this notion of moving really just means the quantities plotted in the HR diagram (the surface temperature and luminosity) are changing. The figure above shows evolutionary tracks for stars with masses of . The tracks for different masses don’t cross significantly and so we can translate a position in the HR diagram into an understanding of the interiors and the evolutionary state of stars. Note how the changing interior structure of the star is indeed reflected in the envelope.

Medium mass Stellar Evolution

For stars with masses , their evolution is similar to low mass stars, with the exception that there isn’t the build up of an isothermal core in the subgiant phase. This is due mostly to the dominance of the CNO cycle during main sequence burning. Stars with CNO cycle burning tend to have convective cores because of their centrally peaked energy generation rate. This means that, instead of building up an inert region in the centre of the star, the fusion at the core will be fed by convection of material from higher up in the star. This means that the fusion will deplete the material in the core all at once rather than building up an isothermal core steadily. These stars will undergo core contraction and move toward and up the red giant branch, but their cores will not become strongly degenerate as the low mass stars do. They thus do not undergo a helium flash and instead have a smooth ignition of helium on to the helium burning sequence on a Kelvin-Helmholtz timescale Such stars are briefly on the Red Giant Branch based on their envelope properties but they do not have the same structure as for a low mass star below.

From this point on, their evolution follows that of a low mass star: helium burning sequence followed by thermal pulsations and the formation of a C/O white dwarf.

High Mass Stellar Evolution

High mass stars are notable because they do not experience a degenerate core during their evolution. Every stage of nuclear burning ends, contracts, heats up and ignites the next heaviest elements of nuclear burning. Of note, such stars, after Helium fusion, will be able to ignite

and other heavy element fusion processes that occur above . These fusion stages all occur at roughly constant luminosity, but the stars undergo significant internal restructuring. For example, when their core contracts and their envelopes expand, their surface temperatures must get smaller meaning they move to the right in the HR diagram. Similarly, when the core ignites and expands again, the envelope will shrink and the star will move to the left. This behaviour is visible in the star track.

Once stars become massive enough to fuse past Carbon, they are also sufficiently massive to fuse up to the peak of the binding-energy-per-nucleon curve at . They do so but ultimately build up an iron core that cannot be fused exothermically. The stars undergo a core collapse and subsequent supernova explosion. This means that the ability to ignite C fusion represents the boundary between stars that will end their lives as white dwarfs () and those that explode in a supernova, leaving behind neutron stars and black holes ().